Afghanistan Part 1 Ishkashem to Sarhad

After narrowly slipping through the gauntlet of the pompous and patronizing Tajik border officials and crossing the Panj aka Amy Dariya aka Pamir river into Afghanistan, my brother and I were picked up by a middle aged Afghan man who worked for the Ishkashem branch of the Agha Khan foundation. At a slothlike pace, the dust coated white jeep carried us along a winding road and up the rocky hill to the town of Afghan Ishkashem. After being dropped off in the center of the village, my brother and I began to feel uneasy, frightened and thoroughly intimidated by our surroundings. The town was little more than a series of narrow muddy streets lined with small bazaar stalls and an occasional mud brick house. As we wandered up the muddy uninviting road, I became riddled with paranoia; I could not help but notice the leathery faces and the soiled clothes of the clusters of men who were now glaring at us with suspicious and curious eyes. My brother voiced his concerns about our safety, … I hesitated before telling him that this village was quite safe and not to worry. I was in Afghanistan……was I just being paranoid? Indeed it is common knowledge that the USA has not won any popularity contests in this country,…. after all it was the USA who was largely responsible for ripping this country to shreds for the last thirty years….but how would this affect my interaction and experience with these people.

I made a mental note: calm down and ignore stereotypes. It is unambiguous that the Western media paints a negative image of Afghans: the Taliban and ‘Islamist terrorist’ are often associated with the image of rural Afghans. This of course is an unfair and inaccurate depiction of the rural, poverty stricken Afghan people. It is common knowledge that often times Islamist terrorists come from expatriate communities in Western states, most of which whom were brought up in middle to upper class households.

I made a conscious decision to meet these curious stares head on. My brother Toby and I began confronting the curious stares by walking directly to each person on the street and saying Asalam Ahalikum, and following this with a sincere handshake and a smile. The fear and unjustified paranoia began melting away with each Afghan we met. Most would open both hands and sandwich my hand with theirs, they would do this with a warm smile and welcoming eyes. The key, in retrospect, was to ignore the nasty images of the Western media and to humanize these people by looking into their eyes and establishing a real and more accurate perception of these people; one based on fact and experience, rather than propaganda and negative imagery. Why does a turban, muddy boots, a weathered caramel colored face, and a striped chapan (Tajik/Uzbek robe) inspire in us a visualization of terrorism and hate? With this logic, should it not be fair that an image of a Chinese person immediately remind us of the atrocities and ideologies of Mao, or should a Georgian person fundamentally inherit the visage and reputation of Stalin?

Ishkashem was really not much of a town, it is a small trading post reputed to be a hub for opium trafficking. Despite the unlikely location, being so far out of my comfort zone began to make me feel alive. The previous eight months I had spent back in the United States had provided me with rest, reconnection, and a thorough reevaluation of the strengths, weaknesses, and existence of the relationships that make me whole. I left the U.S. because of the suffocating feelings of anxiety, monotony, and uncertainty that was chipping away at my soul. Falling back into my old life, and into my old self was becoming a depressing reality………being back on the road and in Afghanistan freed me from these heavy feelings. Peace and happiness slowly returned to me with each step I took into the Wakhan. These feelings were strengthened by the privilege and honor of sharing these special, unique and exhilarating experiences with my little brother.

After shaking dozens of hands and growing a bit more familiar and comfortable with my new surroundings, Toby and I checked into a small quest house across the road from the local police station ( the ‘Aria guest house’). We spent the rest of the evening wandering around Ishkashem gathering supplies for our trek at the local shops. We purchased: 4 head scarves, 3kg of rice, 1.5kg of lentils (bad idea, they take forever to cook at high altitudes), curry powder, 3 rolls of TP, .5kg of raisins, .5 kg of black tea, and a few bags of seasoning powders.

We were not alone at the Aria guest house. An enlightened Japanese guy with an American accent(he went to photography school in the States, and was born there) in his early 30s was also staying with us at our guest house. His name was A.K. Kimoto (his website is: www.spidersandflies.com). AK is a journalist and was in Ishkashem taking photos and gathering information about the problems associated with the widespread opium addiction in the area. Toby and I enjoyed spending our evenings with A.K. and learning about all of his research and experience. Though he considers his home base to be Thailand, he had previously spent a good amount of time in Kabul, and was putting together a self funded academic piece, and photo book on opium addiction in NE Afghanistan. According to A.K., many villages in the area, if not all, have an adult population with a 50% or higher opium addiction rate. In essence, most of the households have at least one opium addict.

*********************

-Side note: over a year later, as I finally type up my journal about Afghanistan, I have found out some unfortunate news. While doing a bit of research on A.K. to make sure his website is still up, I have found out that A.K. had passed away in spring of 2010. His website is no longer working, but you can find tributes to him, and an array of his work all across the web.

I feel compelled to share with you these words A.K. wrote about his time in Ishkashem, I found them online, but have not been able to track down his photo essay yet. I hope to do so.

“I offer to transport the mother and child to a clinic. One of the elders cuts me off before I can finish my thought. He smiles gently as he tells me that the child would never survive such a journey in the cold rain, and anyway, this way of life and death have been repeated for centuries in these mountains.”

Opium Addiction in Badakshan- words of A.K.Kimoto

In the remote North-Eastern province of Badakhshan in Afghanistan, opium and heroin addiction are ravaging isolated mountain communities, and the staggering numbers are only getting worse. In some places, it is said that 70% of the population use drugs in some form, from hashish, to raw opium and refined heroin powder. It is not uncommon to find three generations of a family smoking together behind closed doors.

Traditionally, Opium was used as a cure-all, the magic medicine that could work wonders on anything from back pains to headaches to the nagging cough that every one has during the brutally cold winter months. The residents of Ishkashem, on the Tajikistan border say that it was never a problem before. Now, the situation is changing. In Ishkashem, it is said that at least 50% of the population has a serious drug addiction problem. Other remote villages further down the inaccessible Wakhan Valley are said to have an unbelievable 70-80% addiction rate. Children are born into addiction every day, and thus, the cycle is perpetuated.

I also found one of the last correspondences he had with his close friend James Whitlow Delano ( www.jameswhitlowdelano.com ) regarding his lack of recognition for his work in Ishkashem:

-a pic A.K. took in NE Afghanistan-

“I don’t care about being recognized, and I don’t care if I go through life with no fame to show for my efforts. What bothers me is if people don’t take my latest work seriously. Not for my sake, but for the sake of the people who allowed me to photograph their lives. When was the last time you saw a 4 year old sucking down heroin? Is it not a tragedy? If I can’t do anything to bring attention to their plight, and if nobody cares, then what am I doing with my time and in fact, my life? It was never about awards or anything like that. I thought it was about being out in the world, witnessing things that others don’t see, and sharing these stories with a larger audience. I always said that I do what I do because I only have 2 hands.

6-6-2009 (journal entry)

I feel like shit again. The mutton stew and beans I ate for dinner last night ripped my stomach apart and has left me frail and weak. Food poisoning again! Went to the border bazaar today but was too ill to enjoy it. Popped a few pills that A.K. hooked me up with, and sat on the side outside the rock gate trying to ignore the curious stares and salesmanship of the vendors.

Getting transport and permission to go into the Wakhan Corridor has been a headache. After a lot of haggling with several different drivers, I was able to get transport for $600……….which is an extortionate price for the service. The Hilux will take us from Ishkashem to Sarhad e Broghil, and pick us up two weeks later and drive us back to Ishkashem. We also have a local guy sorting out our permits to get into the Wakhan. He is using his connections in Faizbad and Ishkashem to sort out permission for us to go into the Militarized border zone of the Wakhan corridor and Afghan Pamir. Slept most of the day, too sick to eat, sat around outside with Toby and A.K. most of the evening, drinking tea to stay warm and listening to A.K. talk about the heartbreaking stories of opium addiction and poverty in the villages surrounding Ishkashem. He spends each day with a young interpreter, about 18 years old, and a driver that he picked up out of town for the price of $50 a day, which is not that bad. He tells us that people are usually reluctant to have their picture taken, but he always explains to them that what he is doing is trying to spread awareness, so as to bring help to the area, and a way out of opium addiction and poverty.

7-6-2009 (Journal entry)

It all begins….. Our documents showed up late from Ishkashem, so we were not able to leave Ishkashem until 7am. The first police checkpoint in the Wakhan Corridor was a breeze; our papers got us through without hassle. Down the road a ways, we were stopped at the next checkpoint in the town of Shandar, this scheduled stop was a bit more challenging. After an hour of phone calls, waiting around, and a douse of uncertainty and confusion, the head of police called the commander in Ishkashem (whom he knows well,.. my brother and I had both met him as well), and soon after we were allowed to pass through the gate. Four hours into the jeep ride we reached the town of Qali Panja.

-side note: Qali Panja marks the end of the Wakhan Corridor and the beginning of the Big Pamir)

The local police questioned us briefly before accepting our permits from Ishkashem and Faizbad and writing us another one for Sarhad e Broghil. After the business end was taken care of, they invited our driver and both my brother and I into the police shack for lunch. Rice, bread, and tea…..sitting on the floor with five other soldiers, eating scoops of rice with curled fingers,……though my stomach was still a bit rough, it was a great and memorable experience.

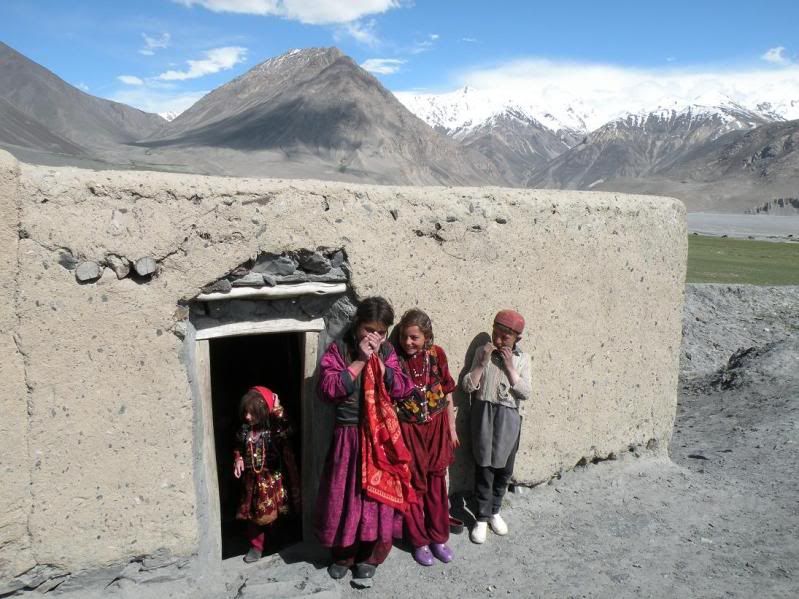

The drive through the Corridor has been amazing, small Wakhi settlements and villages seemed to arise from piles of barren rock, caravans of double humped camels were often visible from the narrow dirt road. The Wakhi people wore bright red clothes and elaborate necklaces and scarves. I began to notice how their pale skin was often chapped and severely sun damaged, this giving them a very unique and weathered look, one that brought about emotions of empathy and sadness. The rugged road that took us the entire way to Sarhad was by all definitions intense. We drove through rivers and deep muddy streams, over deep ruts and mounds, and up and down the steep rocky mountainsides. Wakhi shepards, young and old watched over their sheep and goats, grazing them in the lush grassy fields along the riverside. Centuries if not millenniums old petroglyphs were frequently seen on large boulders near the road. It was a fascinating and beautiful ten hour jeep ride; however, Toby and I were both quite relieved when it ended. We arrived in Sarhad e Broghil slightly after five pm. Sarhad is the end of the jeep trail, it was an exciting realization that we must go on foot from here…

Soon after arriving, we were greeted warmly by our host and a dozen or so of the local Wakhi villagers. All had severely chapped cheeks, leathery skin and glowing eyes. The guest house consisted of a mud and rock shack surrounded by a 1.5 meter mud wall. Just outside the guest house were about forty Yaks owned by a Kygryz caravan. They were all resting and reenergizing after a long journey into Sarhad from their mountain settlements deep into the Little Pamir. The Kyrgyz territories are located deep into the Little Pamir and start with the village of Bozai Gombaz, before this village is exclusively Wakhi settlements. They respect each others cultural and religious differences and seem to have a very solid trade and social relationship, despite the fact that they segregate themselves geographically. The Kygryz are Sunni Islam, while the Wakhi are Ismaili Islam (a branch of Shia). Their language also differs, but from my experience, they all seem to know each other’s languages, as well as Pashtun.

Sarhad can be described as a serene location. Sarhad is made up of a series of mud shacks and low grassy hills. To the south is a wide flat riverbed interrupted at times by generally shallow streams. Beyond this is a wall of jagged snow peaked mountains belonging to the Karakoram Range, the peaks of these mountains generally representing the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan. At the eastern tip of Sarhad is where three of the four highest mountain ranges in the world collide with breathtaking elegance. To the east of Sarhad you can see the Hindu Kush on the left, the Pamir in the center, and the Karakoram to the right. I don’t believe I have ever stood in a location exhibiting as much natural beauty and cultural vibrancy as Sarhad e Broghil. I must note however, that the Wakhi people of Sarhad are visibly worn down by the struggles of everyday life. The infant mortality rate in the Wakhan Corridor is claimed by many to be the highest in the world (163+/1000).

-Reference:

-“The human population of the whole Wakhan/Pamir area-both settled Wakhi and nomad Kyrghyz-suffer

from a compound of problems including chronic poverty, ill health, lack of education, food insecurity,

and opium addiction, arising from the remoteness and harshness of their environment and the lack of

resources and facilities”. (UNEP 2003 http://postconflict.unep.ch/publications/WCR.pdf)

After a quick meal, my brother and I went on a walk around the village trails. We stopped briefly on a large burial mound overlooking the river and expressed to each other the overflowing joy we felt to have finally reaching the trail head.

Here are a few pics:

Men in Iskhashem

On the road leaving Ishkashem…

Pics from the jeep trail:

Lunch at the Police Station

My Brother Toby pictured to the left:

The people of Sarhad e Broghil:

Photo credits go to my brother Toby on a few of these, notably the one below.

Day one! Hitting the trail………..destination over that pass in front of me

Videos:

Ishkashem panoramic shot:

Border market in Ishkashem. Tajiks and Afghans meet at the border once a week to trade with one another:

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home