-The Hindu Kush-

-The Hindu Kush-

5-11-2008

My body was slowly falling apart and I feared for the worse as the bus pulled out of Gilgit at 7:30am; my head was pounding and my stomach was aching for food, but the thought of consuming anything other than soft fruit overwhelmed me with intense feelings of nausea. In this condition, how was I to survive a 15+ hour hot, cramped, and bumpy bus ride? I have been shedding pounds at a frightening rate throughout my journey; I currently weigh about 180lbs, a full 35lbs less than I weighed 3 years ago before I left the USA for my Peace Corps assignment. The major issue being that I was relatively skinny when I left; which means now I am simply unhealthy.

Food poisoning, sporadic eating habits, and overall malnutrition are excellent ways to lose weight and help bring out your inner skeleton. I should create a weight loss program when I return home; food poisoning is the perfect way to unite bulimia and anorexia together in order to create the perfect combo of rapid weight loss without the psychological issues that accompany both. One rotten sandwich a month for 6 months………and I guarantee you will shed those pounds, but always be anxiously waiting for the diet to end!

The bus driver skillfully drove along the sketchy partially washed out road, dodging large boulders, gushing streams, and half cleared landslides. The road cut along the canyon wall with incredibly sharp precision that left very little room for error. We were never far from a fatal accident as we constantly had to slam on the breaks to avoid head on collisions with oncoming cars. I kept my sanity by putting the situation into perspective; this man does not want to die, nor does he want to kill everyone on the bus, and he obviously knows the road and its limitations to a much greater extent than I. Still, looking down 300ft cliffs that are only inches from the edge of the bus is frightening. The road was a maximum of only a lane and a half wide in most segments, and was only partially paved.

While driving along the windy road, I began seeing inspirational words written with white spray paint along the stony cliffs. The words were written in both English and Urdu and were usually 1-3km apart. The messages read: “Serve Nation”, “Educate Your Children”, “Develop Your Area”, and “Help the Tourists”. I interpreted these messages as a sign of forward progression for Pakistan. The people of Pakistan do not want to fall into the fiery pit of self destruction and intolerable extremism. They appear to be striving toward being a fundamentally religious but progressive nation; a nation free from epidemics of war, hate, pain, ignorance, and political turmoil; a nation that strives to pull away from the very things that have been crippling their Islamic counterparts.

At 11:50am our bus peeled off the road and stopped for lunch at a small mud/wood shack alongside a shallow river. I was a bit confused about the eating situation, but thankfully was taken under the wing of the man I was sitting next to on the bus. I followed him into the shack where we left our shoes at the door, and proceeded to sit on the floor surrounding a straw matt; soon after, we were all served vegetable curry, rice, chapatti, and milk tea. I felt a bit strange, awkward, and out of place; however, moments like these are what I truly thrive on and strangely enjoy. The inquisitive man next to me spoke broken English and looked about as fair skinned as any European I had ever met. He had light brown hair, a thick colonial mustache, and green eyes. The only part of his appearance that made him appear ethnically different was his Chitrali cap and his shalwar kameez.

I definitely was the oddball of the crew; most of the men around me had long thick beards and sported Chitrali caps with their shalwar kameez (traditional clothes). The men in the shack stared at me intimately and seemed to be discussing me intensively as we ate. I had no choice but to smile occasionally when eye contact was made, and recognize that I was simply a weird looking guy, wearing weird clothes, and in a land where reverence and cultural conformity is incredibly important. If I were dining at a restaurant in the USA, and a Kenyan Bushman walked through the door (wearing traditional clothing) and sat beside me at the table, I would most likely inadvertently analyze the man and discuss his lack of conformity. From day one I have been completely aware that I am merely a guest in the countries I visit, and it is my responsibility to respect each land’s culture, religion, and social norms despite how radically they may differ from my own.

After lunch we all boarded the bus and were soon on our way. A couple men on the bus had spent their break fishing down beside the river; one of the men was now holding three small trout gilled by a thin twig. I thoroughly enjoyed the company of the man next to me; we discussed a variety of topics but did not dive too heavily into anything much deeper than small talk. It was pleasant to discuss simple things like family, work, and recreation; as opposed to international politics and President Bush.

I was only able to choke down about half of my lunch, which instead of curing my hunger and soothing my aching stomach, actually made me feel worse. I found it increasingly difficult to enjoy my surroundings and to take pleasure in the moment. I was traveling an unknown road, a road of vast cultural significance and natural beauty, but unfortunately was not in the proper condition to soak in the atmosphere and properly enjoy it.

We constantly picked up villagers and dropped them off as the bus slowly made its way along the increasingly shabby road. I noticed that several of the village women we picked up had dyed orange decorations on their hands and wrists, their children had the same markings. The dye on their hands is similar if not identical to henna ink, and is called “mandee” in Urdu. Some women had it decoratively painted on their hands, while others had their entire hands sloppily dyed orange. All of the village women wore traditional burkas (decorative long baggy shirt, and pants) and covered their hair with colorful shawls. The Pakistani women would often cover their faces with their shawls and turn away the moment they caught a glimpse of me. I guess that is what I get for being an infidel.

One of the steep rural towns (Golokmuri) appeared to be having some sort of festival, perhaps it was a wedding. The whole village seamed to be celebrating together on a grassy hill resembling a natural amphitheatre. Further down the road was the town of Gurdu, where villagers stocked the bus inquisitively as it drove through. The villagers of Gurdu wore shabby, tattered clothes and overall looked quite filthy. Despite the villagers’ rugged appearance, their smiles radiated strongly enough to exhibit an outline of happiness and contentment with their rural mountain village lifestyles. When the bus stopped in Gurdu, a woman boarded the bus holding a small child with her face painted like a batman character. Speckles of a black tar like substance was caked around both eyes, cheeks, and her forehead like a lone ranger mask; after later inquiries I found out that this was considered to be healthy for the baby, because the black substance attracts the sun and keeps the baby warm. We were in fact high on a rugged mountain pass, where the air was considerably cooler than the lower valleys.

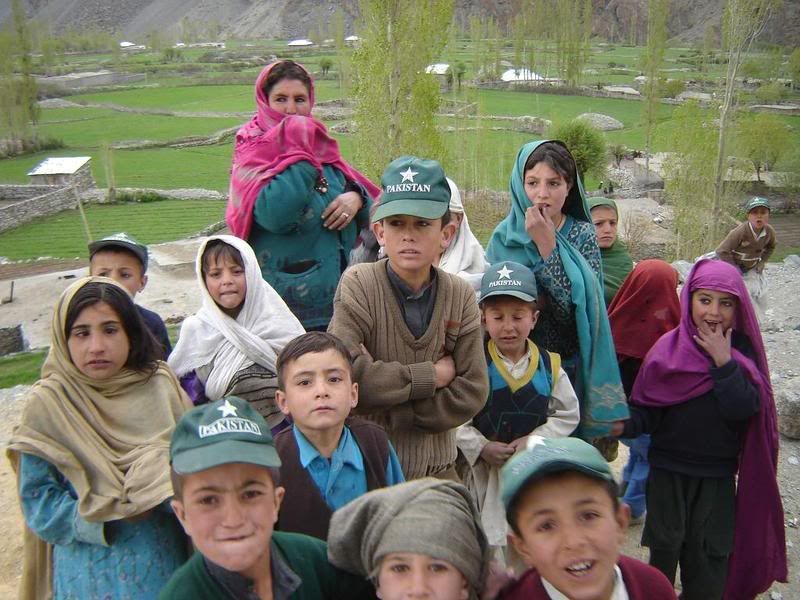

The scantily paved road officially turned to dirt and rocks at 2:30pm, which resulted in the slowing of our already sloth like pace. We were now traveling less than 15mph along the steep bumpy road up a rocky mountain pass. I witnessed several large families having picnics amongst their livestock on the grassy rolling hills that surrounded the road. Throughout the mountain passes we would drive in the vicinity of small villages where the children would spot me and enthusiastically run along the bus in order to catch a glimpse of the strange looking foreigner. Many of the children wore green baseball caps with “Pakistan” and a white star printed on the front. When the bus occasionally stopped, I noticed that the villagers greeted each other by first the woman kissing the man’s hand and second the man kissing the woman’s hand. I poked my camera out the window and took a couple of photos of the kids surrounding the bus, a few of the young girls seemed repulsed, scared, and furious, while others smiled and eagerly crowded toward my window. Their faces were dirty; their clothes near deterioration, and a surprising number were cross eyed (which often suggest incestuous behavior…….)

The rural mountain villages along the isolated dirt road consisted of clusters of mud shacks alongside lush green fields of grazing yaks. The people that gathered around the bus at each stop looked weathered, worn down, and had dry chapped hands. Despite their physical appearance, they did exhibit an exuberance of happiness. Each person returning to their village was greeted with ecstatic reactions and an abundance of smiles. Many of these villages were far from electricity, and generally seemed to be self sustained.

The village at the top of the pass was called Shandur and consisted of little more than a polo field and a tea shack. Apparently Shandur hosts several important polo games each year. Leading up to Shandur was a series of steep grassy marshes filled with grazing yaks. A couple of times we dropped off shepherds equipped with camping gear at desolate fields tens of miles from the nearest village. Shandur was surrounded by rolling hills of lush green grass and lined with massive snow capped mountains. The Yaks grazing near the road would lift their bushy tails and athletically sprint away from the road as the bus slowly crept up the hill. I was actually quite surprised to see how agile and athletic the yaks were. They would raise their tails and sprint around the fields like hyper gazelles; quite impressive for such a large beast.

After a quick tea break in Shandur we began our descent into the desolate and seemingly inaccessible Lasper Valley. The road began to get sketchier and sketchier as we made our way down a frightening series of cut backs. Several times the bus driver had to send his assistant outside in front of the bus in order to guide us along the narrow road. We were literally a 7inch landslide away from disaster and death. The 300ft cliffs on the edge of the road made my heart race with fear. This was by far the most dangerous road I had ever been on. The road was cut into an unstable mountainside of falling rock, and was barely wide enough to hold a vehicle. The collapsing sections of the road produced the frightful appearance of a serrated knife.

I breathed a sigh of relief when we reached the village of Mustouch, home of the 5th and final police check point before Chitral. Each time there was a police check point; I was forced off the bus to fill out a form (Visa #, Passport #, destination, etc.) and answer a few simple questions. Most of the police I encountered along the way were friendly and gave me little hassle.

It was now 7:00pm and we had traveled only 262 kilometers from Gilgit. Which means the bus was traveling at an average speed of around 15 miles per hour.

After the police check point the bus continued for another 20 minutes before stopping indefinitely. Apparently this was the end of the road, but we were still 114km from Chitral. The road was too windy, rough, and narrow to handle a small bus; from Mustouch onward the roads were only accessible by jeep.

I was absolutely exhausted by this point and I felt as if I had a stomach full of jagged rocks. My options were to either stay in Mustouch for the night and catch a jeep to Chitral in the morning, or to simply keep the party going and continue my journey. I decided to go with the latter; I was horribly fatigued, but wanted to get it all out of the way in order to wake up fresh and rested in Chitral.

I was not actually hungry, but my painfully empty stomach yearned for substance; so I decided to try and track down a bite to eat. After a quick exploration of the desolate mountain village, I came across an old wooden shack selling groceries and shoes. There were very few consumables in the place besides peanuts and stale cookies;….I opted for the dusty box of milk I scoped out on the floor near the worn down combat boots. Boxed milk never really goes bad does it? The 8oz box of milk was covered with dirt and was a bit rough around the edges, but I had irrational confidence that it was legit, so I made the purchase. After pounding the box of fermented dairy poison I was off to find a ride to Chitral.

I easily tracked down a man with an extra seat in his old beat up land cruiser and hopped aboard. We left Mustouch at around 7:30pm, at which point I soon discovered that the jeep trail to Chitral was pretty much insane. We drove along the thin barely visible jeep trail, over the top of landslides, through deep streams, and around recently fallen boulders that obstructed our path. The ride was bumpy, terrifying, and slow going, however we were definitely making progress.

9:05pm- we stopped in ParWak, a desolate village consisting of a small makeshift gas station and a few mud shacks. I actually felt quite uneasy about this stop; my mind began racing wildly as worst case scenarios were uncontrollably bouncing around in my skull. Why were we stopping? Perhaps so they could take me into a shack and decapitate me after lecturing me about my “anti-Islamic American Government”. Of course my mentality at this moment was paranoid, ridiculous, and skewed, but in the back of my mind I was fully aware that stranger things had happened.

Should I have felt comfortable with the situation? Is it unnatural for an American to feel a bit uneasy while alone in the darkness of desolate North West Pakistan? I followed the four other men from the jeep up a hill and into a small mud shack with no door. As we entered, the room suddenly became deathly silent. What I visualized upon entering the shack was a mirror image of what the Western media had pounded into my mind. Here was a room full of dirty, bearded, terrorists, with horrible extremist intentions and hearts as cold as ice. Why was I unable to see a room full of kind, gentle, friendly men, conversing about the same sort of life issues we all do while congregating around friends at our local American dive bars? I later felt horrible, guilty, and disgusted about my racist, ignorant, and unfairly presumptuous first impressions.

The dimly lit room was filled with middle aged Pakistani men with dirty clothes and shaggy dark beards. They were all sitting on a foot high wooden platform covered by a dirty Persian rug, smoking hash cigarettes and quietly conversing amongst themselves. At the end of the platform was a prehistoric television set tuned into what looked like the Indian version of Baywatch. Even though the reception made the picture almost unwatchable, several of the men stared at the television with undivided attention. As I stood in silence observing my new surroundings, I could not help but contemplate the possibility that I was in a room of uneducated militants with very strong opinions about the Bush administration.

After about five minutes of suspicious stares, and verbal inquiries directed at my driver, the men lost interest and went back to their Bollywood Baywatch. At the end of the shack was a small mud stove where they were cooking vegetable curry and rice. As I slowly approached the stove an old hunch-backed man stood up off his 6 inch stool and with a weathered smile, graciously offered me his seat. Moments later I was handed a plate of food and a cup of milk tea. The men cordially smiled as they intently observed me consume my gift.

My stomach was in poor form as I desperately tried to choke down each bite of the dry, barely consumable rice and vegetable curry. I felt awkward and rude not being able to finish my meal, so I discretely ditched my plate of food and snuck out the backdoor into the darkness. I awkwardly hid outside in the bushes near the jeep until my jeep-mates were ready to hit the road again. We were back on the road at 9:30pm, tearing through the moonlit trail with frighteningly aggressive tactics.

The next leg of the jeep trail was periodically obstructed by large herds of sheep. I am still unsure whether the shepherds were beginning or ending their day. Why where shepherds herding sheep at 11:30pm? Was it possible that they where working the shepherd graveyard shift? Is there a shepherd graveyard shift? Anyways, my driver became increasingly frustrated by the obstructive flowing rivers of sheep, and constantly yelled out his window at them. Judging by the intensity of his tone and body language, I believe that my driver was threatening the shepherds with some form of violence for obstructing the road.

At about 11:45pm the dirt road finally ended and a paved road began; within a half hour we had arrived at the largest city in the Hindu Kush, Chitral.

The streets of Chitral were quiet, empty, and dimly lit by street lamps. I was dropped off in the center of town, and within 30 minutes was able to find a cheap hotel room to lay my head ($4). The room had peeling green wallpaper, one small cot, a rock hard pillow, and raggedy off-white sheets. The 8x10 windowless room was blazing hot and had one of the most disgusting toilets I had ever seen. It was now 12:30PM………and despite the condition of my hotel room, I felt relaxed, peaceful and ready to sleep. After a cold shower to cool down, I hopped into bed and almost immediately fell asleep.

At 2:30am I woke up suddenly after having a horrible nightmare that I was drowning in a pool of dark sludge. When I woke up I was desperately gasping for air and was choking on a mouth full of vomit. Stomach juices disgustingly sprayed across my chest, legs, and bed as I stood up frantically coughing up the rancid contents of my throat and mouth. My balloon like stomach was bloated and stretched out to the point of bursting. I was scared. The next 6-8 sleepless hours I puked, burped, farted, shat, and laid in my bed painfully deflating. The situation was all very strange, terrifying, and uncomfortable. I was actually afraid to fall asleep because I thought I might die. Perhaps it was a bit silly to think that, but waking up choking on your own vomit is frightening.

5-12-2008

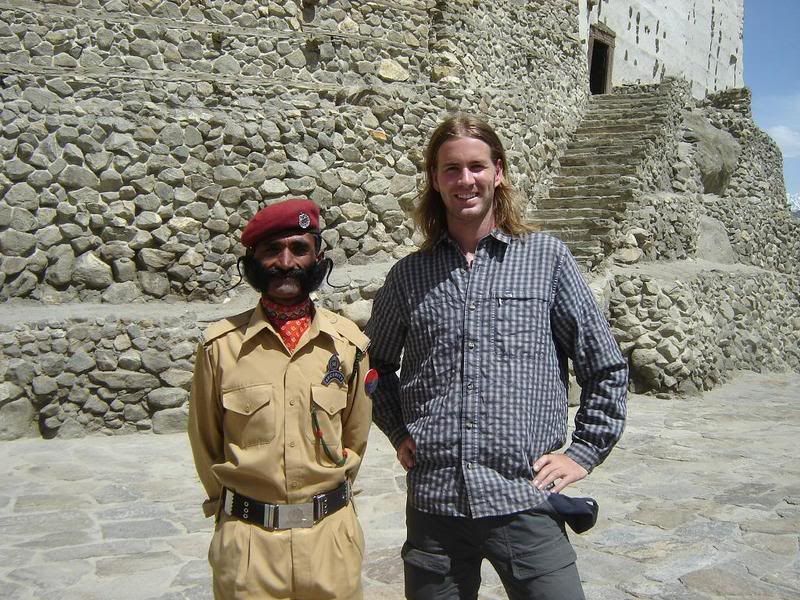

At 11am the young hotel owner suddenly burst into my room and was shocked to see me still lying in bed. I abruptly responded by yelling at him and telling him to get the hell out of my room. I guess that was my wake up call. After a cold shower, I consumed a handful of salty cookies, pounded a quart of iodine flavored water, and was on my way out the door. The streets of Chitral were now bustling, loud, and packed with people. I was in the middle of a large bazaar with shops selling everything from naswar (chewing tobacco) to machine guns. As I wandered through the busy streets of Chitral, I was constantly presented with curious stares intermixed with warm smiles and guiltless curiosity. Eventually I made my way past a cluster of armed soldiers and across a small bridge to the jeep-station on the far end of town.

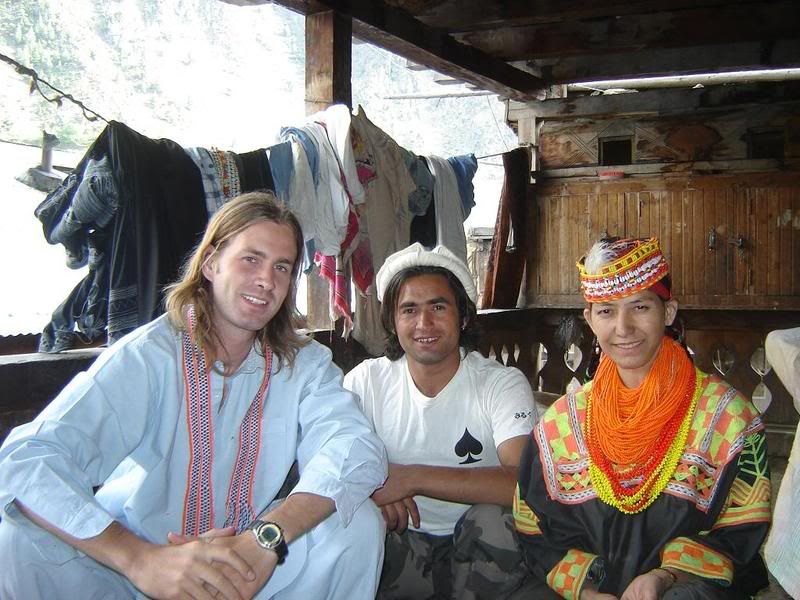

Upon arrival, I was quickly befriended by Timuk a 21 year old college student from the Kalasha valley. He had been studying economics and English in Peshawar and was eager to converse with me in English. With pride and enthusiasm he began telling me all about his village of Bumboret and how I should definitely visit the Kalasha Valley. His stories intrigued me and immediately sparked my interest. What was the Kalasha Valley? Why had I never heard of this strange place? Timuk told me to take a jeep to the Kalasha valley and that he would meet me the following day to show me around his village. I accepted his offer without hesitation and immediately boarded a small double-cab pick up truck heading to Bumboret.

{The Kalasha valley consists of three small villages tucked away deep in the folds of the Hindu Kush. The total population of the three villages (Bumboret, Rumber and Birir) is around 3,500 people. The Kalasha valley is extraordinarily unique because of its one of a kind language, religion, and culture that has been incredibly maintained throughout its history.}

I was astonished by how many people we could fit in the pickup truck. Five other people and I sat facing each other on bench seats in the bed of the truck, 6 people occupied the seats inside the truck, and 6 other people stood on the bumper hanging off the back. It was quite impressive that this truck was able to take such abuse; we were like a bunch of monkeys clinging to a safari jeep.

The Hindu Kush was absolutely beautiful. The road between Gilgit and Chitral seamed to be geologically forced within one long jagged mountain valley. However, once we entered Chitral the canyon magnificently open up into a series of deeply cut mountain valleys surrounded by enormous hills and dominant snow capped peaks. The area was lush, green, and justifiably under populated.

It is hard to believe that a place like this still exists in the world; an area so desolate, inaccessible and implausible that a community as culturally and ethnically diverse as the Kalash has been able to remain intact and avoid the sharp destructive claws of globalization and religious oppression. How were the people of the Kalasha valley able to avoid religious and cultural coercion and persecution throughout their long history? How were they able to avoid urbanization and forced conformity? My only hypothetical answer to this question is that the tremendously isolated location of the Kalasha valley has adequately preserved their culture by forcefully maintaining a unique, simple, desolate, but sustainable lifestyle of the villagers.

After a long stretch of wavy road that plowed deeply through thick green vegetation high along the mountainside, we began a descent into the small barely accessible town of Ayun (20km from Chitral). Ayun is situated at the base of a valley, between a large river and the sharp, rocky mountainside that breaks slightly making a heavens gate entryway to the Kalasha Valley. Ayun at first glance(my) is a very primitive looking town of dusty dirt roads, shale roofed mud shacks, and skeptical locals. Groups of tired and weathered looking men squatted together in front of the meat markets and curiously observed the passers by. Most men on the streets of Ayun wore dirty shalwar kameezes, Chitrali caps, and large checkered turbans around their necks.

After passing through Ayun we began to climb higher and deeper into the mountainside on an increasingly narrow dirt road. The road followed the rim of a steep canyon on a trail blasted out of solid rock. After about 30 minutes we arrived at a police check point where I was asked to fill out a form, pay a registration fee, and answer a few questions. Apparently it was mandatory that I register with the police station in Chitral before entering the Kalasha Valley. After a bit of confusion on both ends of the conversation, the police decided to let me through as long as I promised to return the following day to Chitral and register.

The rocky dirt road cut gently onward through the narrow canyon to an increasingly desolate location. The road was barely wide enough for a jeep, and often hugged the edge of 100-150ft cliffs. Parts of this road were down right terrifying, but being able to look forward and see just how deep we were into such a marvelous canyon was amazing. I felt as if I were driving into the unknown, a place where no white man had gone before, a true expedition. Of course this was far from the truth, but nonetheless being in such an isolated area and foreseeing cultural discovery and adventure, raised my spirits significantly and enchanted my soul.

The scenery became more and more beautiful as the canyon began to open up into a lush green valley of fruit trees, grassy fields, grazing goats, and sporadically placed mountain shacks. I had no idea what to expect when entering the Kalasha Valley; I only knew that it would be culturally different, and situated in a very beautiful, lush, secluded mountain valley.

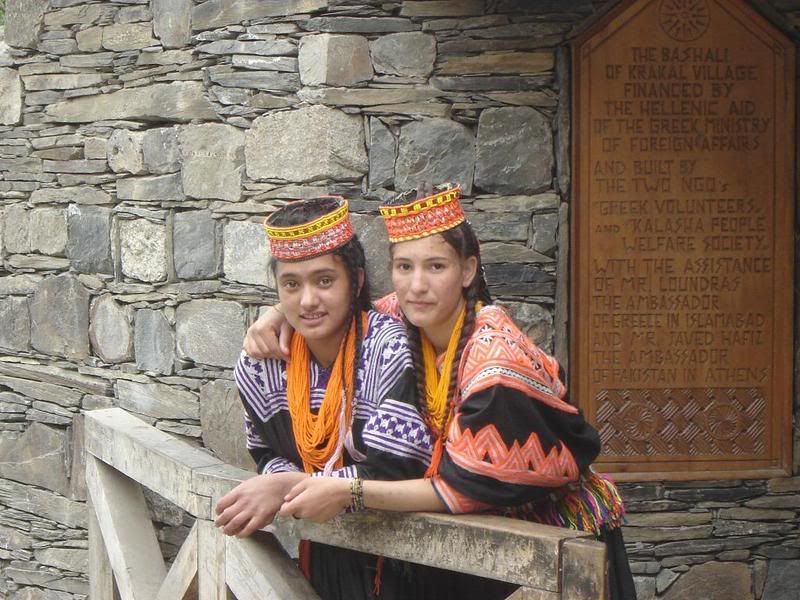

The first time my eyes gazed upon a Kalash woman I felt indescribable exhilaration. Through the thick plum trees about 30yds away from the road, I saw an old woman standing like an angel near the edge of her garden. She had long, dark, exotically braided hair, with a colorful, beautifully beaded headdress that wrapped around her head like a halo and draped down her back. She wore many bright colored necklaces around her neck and a long black dress edged with thick colorful patterns. Something about that opening visual really moved me. I felt that I had finally seen something pure and different, something so unique that it shattered the MTV-CNN-FOX-CORPORATE- bullshit of my generation, and produced a glimpse of cultural purity that I had never seen before. It was like going on a long hike through a desolate mountainside and suddenly coming across an American Indian wearing a beautiful headdress, and traditional clothing; but this Indian was of a lost tribe, unaware of the pushes and pulls of today, unaware of the unavoidable cultural oppression and dilution of our modern world. Imagine that this Indian was part of a tribe that was located so deep into the forests that it had been completely untouched by the outside world, and able to remain free from the poisons of our modern, corporate, greedy, rapid paced, ugly, urbanized and selfish modern societies.

I am not so naïve as to think that I had discovered a culture unscathed by modern society, however I am convinced that the Kalasha Valley is one of the few places in the world that has remained culturally pure throughout the years, and I pray that this will not soon change.

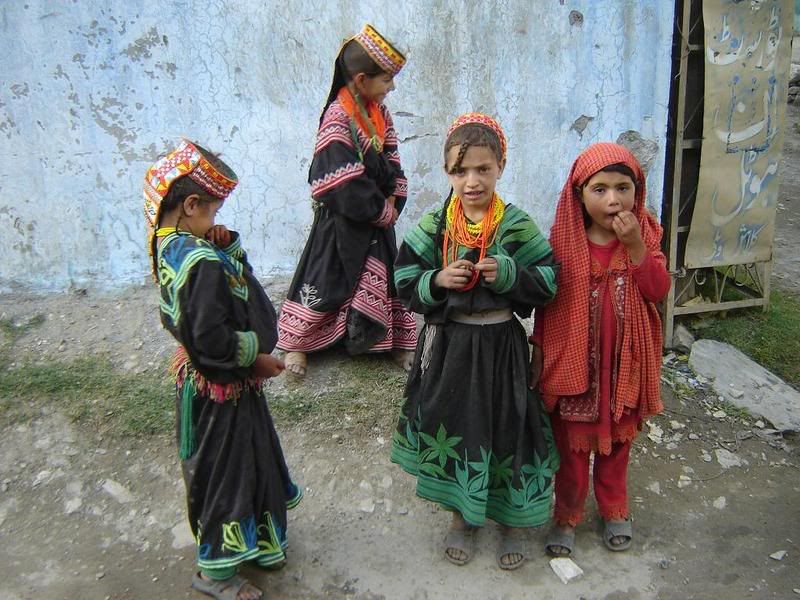

After being dropped off at the bottom of Bumboret, I slowly walked up the dusty road soaking in what I could of the magical atmosphere. Each time I saw a local villager, I was taken back by their stunningly decorated attire, and their ability to completely ignore my presence. Children ran up and down the dirt road playing with a short stick and an 8inch wide wire wheel. They would guide the wire wheel upright while moving it along with their stick. The girls would giggle and play together in the grass fields along the narrow stream that zigzagged every so often across the main road. Women were working in the fields and socializing while washing laundry along the river bank. Clothes were scattered amongst flat, bleached white river rocks, radiantly drying in sun. I find it a quite challenging to describe in words just how uniquely Kalash women present themselves. Their clothing and accessories are made out of bright joyful colors; their hair is braided into a very distinctive and exotic style. The hairstyles of the young girls are even more peculiar; they often have a shaved head except for two long braids, one on the front, and one on the back of their heads. The front braid is always tucked behind one of their ears and draped down the side of their kneck. The Kalash men wore regular Shalwar Kameezes and Chitrali caps as they rebuilt parts of the road and looked after sheep along the rocky hillside. The only cultural difference in their clothing was the feather they wore sewn into the front of their Chitrali cap that signified they were Kalash(not Muslim).

My initial observations of Bumboret exceeded my expectations significantly. I immediately began to realize that this would by far be the most interesting and significant section of my journey. In a way, being in the Kalasha valley gave me a boost of energy and added drive to continue my exploration; but it also presented a peak of greatness and amazement that perhaps I will never again be able to reach.

After a quick observation of my surroundings, I came across a small guest house where I dropped off my bag and decided to check in. There was no electricity or plumbing, but the price was right and it included two meals per day. Despite the excitement and exhilaration I was feeling as a result of my newly found paradise, I was exhausted from lack of sleep, and a bit run down with sickness. After checking in I promptly laid down on my bed and fell asleep. I woke up around 7pm and decided to wander further up the road and explore the area.

The narrow valley had only one poorly maintained jeep trail that cut through the center of the village. The heart of Bumboret is a large cluster of old wooden houses intertwined like shingles on the steep hillside. The houses in the center of the cluster have thick mud/wood roofs that the locals use to congregate and socialize. Each small house appears to have been put together centuries ago using an age old traditional carpentry technique. The large pieces of dark wood used in the construction of the houses, give the homes a very rustic, primitive charm.

5-13-2008

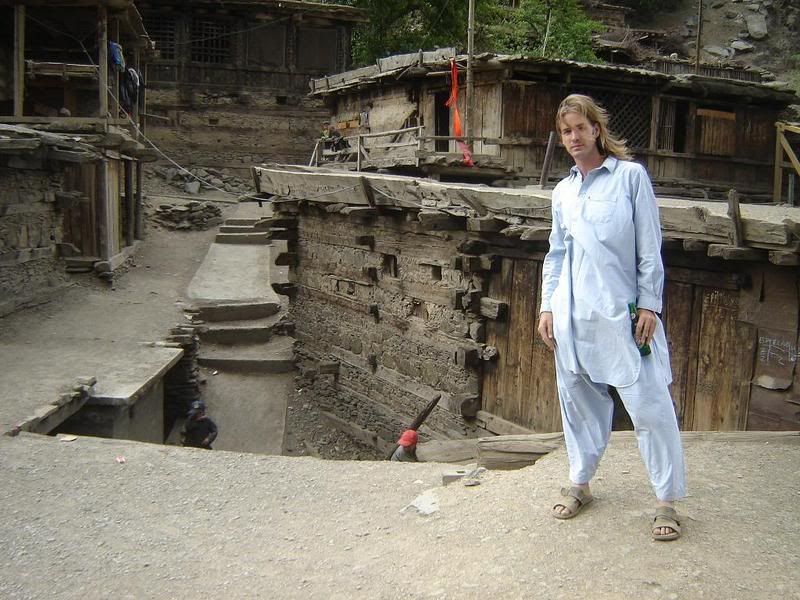

I woke up at 5:30am, ate a quick breakfast and was in a jeep heading to Chitral by 6am. At 8am I arrived in Chitral and was immediately befriended by a young Chitrali cab driver named Mohammed. He guided me to the police station where I spent the next hour shuffling from room to room filling out forms and answering questions. After registering my Mohammed and I did a bit of clothes shopping at the local bazaar. I managed to pick up a baby blue shalwar kameez and another Chitrali cap for under $10. I have personally found that it is prudent to stay low profile in Pakistan. Wearing local clothes, and being cautious and discreet while taking photos is a good way to keep from making waves. As an American in Pakistan, the last thing I want to do is stand out. I have found that having long hair, wearing local clothes, and taking very few photographs has helped me maintain a low profile. If I had a shaved head, wore western clothes, and ran around photographing everything; perhaps my experience in Pakistan would not be quite as pure-safe-pleasant.

I quickly made it back to Bumboret and past the police check point without any problems. I was happy to have made it back to the Kalasha Valley in time to view the beginning of Kalasha Valley’s spring festival dubbed Joshi.

At around 5pm I began walking up the road to the heart of Bumboret. I came across a small green field near a narrow creek where local villagers were practicing their cultural dances. Young boys methodically pounded large drums as the young girls danced together in harmony with interlocked arms. While sitting on a small rock at the edge of the field and observing the dancing; my Kalash friend Timuk slapped me on the back and sat down beside me. He told me that the women were gathering flowers on the mountainside and would be parading down the road soon. Timuk spent the next hour sharing his culture with me by explaining many of the Kalash customs and traditions.

This is what I learned:

- The Kalash people live only in the 3 villages of the Kalasha valley.

-Language: the people of the Kalasha Valley speak a unique unwritten language called Kalash.

-Religion: They practice a pagan religion called Kalash. They often sacrifice goats for various reasons to please their god Mohadeo. Most serious religious ceremonies take place at their spiritual house called the Gestikan. The Gestikan is full of animal figures and effigies, and is a place commonly used for birth and death rituals. The Malosh is a holy place near the village where sacrifices are commonly made to Mohadeo. They believe in only one god, but a god with several deities that protect various aspects of life.

-Birth: - A holy ritual is performed at the Gestikan and a goat is sacrificed.

-Death:- if the deceased age is 10 years or older, all three Kalash villages will congregate and sacrifice 50-70 goats and a few cows. The body is placed in the Gestikan for two days, villagers visit the body during this period in order to pay their respects. The leaders/elders of each village will give speeches about the life and accomplishments of the deceased. The villagers then have a large feast of cheese, bread and joosh (boiled goat), they use up 40-50 bags of flower during the celebration. They also drink their fair share of home made wine and brandy during the funeral ceremonies. Bodies are buried in the village graveyard called the modokjol.

-Women: wear traditional clothes at all times. They produce all their clothing by hand and are all masters of their craft. Small tattoos on the faces of women are a sign of beauty and maturity.

-All women are considered unclean during menstruation (5-6 days a month), and are forced out of their homes to a small female only house called the beshali. The beshali has a yard but there is a line in the yard that they are forbidden to cross until they are “clean”. They are not to be touched by anyone during this period, and are not allowed to converse with other men.

-After childbirth, the Kalash woman must go through a purity ritual, and is sent to the beshali for ten full days.

-Marriage: Kalash villagers usually get married between the ages of 18-22.

Women are expected to maintain their virginity until marriage; men are not.

People get married only after falling in love, marriages are never prearranged. The man will surprise the woman and her family by randomly kidnapping her, after they elope the families will then meet. The families then have a month to get to know each other and to agree with the marriage and decide the dowry (gift from groom’s parents). After this is settled, they will perform a ritual, and sacrifice a goat to make the marriage official.

Festivals: The Kalash celebrate several festivals, most have to do with the beginning of harvest seasons. Timuk’s favorite festival is Chomus. It takes place December 18-20, and each family must sacrifice a goat for the celebration. The festival is full of dancing, eating, and drinking mass quantities of home made wine. (I imagine this is why Timuk likes it so much).Joshi festival is the festival of spring, and lasts an entire week. The heart of the festival is between May 13th-16th. Each of the three villages hosts one day of the festival with a large dance and celebration.

-Bumboret is the largest of the Kalash villages, and Birir is the smallest(Rumber is obviously somewhere in the middle).

Where on earth did they come from??????

-There are three accepted theories to this question, however they have all remained inconclusive.

1) They are descendants of Alexander the Great’s soldiers, which makes them more or less Macedonian immigrants. This is plausible because Alexander the Great did in fact trample through Northern Pakistan sometime during the 4th century BC. He was also known to have occasionally planted groups of soldiers to start cities throughout his conquered lands. And of course the Kalash people generally have quite fair skin

2) They are from Asia, and migrated from the Nuristan area of Afghanistan.

3) The Kalash people migrated to Afghanistan from a place in South-Asia that the Kalash people call Tsiyam. The land of Tsiyam is talked about in Kalash folk songs, and their epic stories.

After a fascinating and very educational conversation with Timuk, we started walking up the road toward the Kalash women. We soon met them on the narrow dirt path and watched them slowly drift by with beauty and grace. The women were singing a very serene mantra as they marched down the hill in unison. While gliding in sync, they clutched each others shoulders with one hand, and carried a bouquet of yellow mountain flowers in the other. I felt privileged to be with my friend Timuk ,because my association with him allowed the Kalash women to feel at ease, and in essence trust me enough to photograph them. Earlier in the day the same Kalash women would shyly turn away when I approached them. Now they were smiling at me and even posing for photographs. Two of Timuk’s sisters were part of the mini-parade, so being a buddy of Timuk’s really got me in the door. We followed the beautifully dressed women down the hill and to the grass field where everyone danced in unison to the melodic beat of the drums. It felt amazing to be the only tourist experiencing such an incredible event.

Later in the evening, Timuk and I walked around his village discussing life, love, and the cultural differences of our two countries. We ended up in the home of his aunt, an old wooden house in the center of the giant hillside colony. The house had two small dirt floor rooms and a small covered patio. Only one of the rooms had a door and was furnished with cots to sleep on. The other small room contained a few wooden trunks, a couple small stools and a tiny stove. Timuk’s Aunt’s home was very simple, yet practical. We sat on small wooden stools on the patio and drank home made apricot brandy while snacking on walnuts and dried apricots. Our conversation was very limited due to the massive language barrier, but thankfully, kindness and hospitality can be expressed without spoken words. Timuk’s Aunt generously presented me with a beautiful thin decorative chest-band as a gift for being a guest in her home. I was blown away by her amazing generosity and warmth toward such an outsider like myself.

Next we headed to Timuk’s house where I was greeted cordially by his mother and sisters. The house was quite similar to his aunt’s home, but had one small extra room for socializing. The room was 8x8ft and had a small hole in the ceiling that let in enough sunlight to light the room (neither home had electricity or plumbing). The dark wooden walls were covered with pictures of bollywood actors in revealing clothing. I was invited to sit down on the small straw matt of the “social room” and was immediately presented with walnuts and homemade wine. My new Kalash friend kept cracking the walnuts for me and presenting me with the flesh of the nut. He always treated me as a brother, and displayed kindness and generosity graciously. Not long after sitting down, Timuk and I made a toast and pounded our glasses of wine. He followed the toast by pouring us each a glass of homemade apricot brandy. A few minutes later his mother entered the dimly lit room and presented me with a blue and yellow bracelet as well as a pink and orange chest-band. After the evening winded down, I gratefully thanked my hosts and made plans to meet Timuk the following morning.

Words cannot describe how incredible I felt as I walked home from the heart of Bumboret. I had spent the evening as a guest in the homes of some of the most hospitable, kind, and unique people I have ever met. Despite feeling relatively ill throughout the day, I feel confident in saying that this was by far the most pleasant and memorable night of my journey thus far. I fell asleep feeling a strange almost spiritual sensation that consumed my mind and body. I was feeling a level of contentment and blissful happiness that I have not been able to attain since my early childhood. It sounds a bit strange to be affected this way by a simple evening, but in reality this was the zenith of my journey. It was a moment of bliss that made all the food poisoning, bumpy bus rides, horrendously long train rides, frozen midnight walks, cold stares, police shake-downs and repetitive political debates worth it. Traveling long distances, months at a time along unpolished and unreliable paths is ridiculously challenging. But in the end; the experience, knowledge, and insight gained is absolutely priceless. People explore the unbeaten path despite enduring endless amounts of self inflicted hardships simply because “the ends always justify the means”.

5-14-2008

I woke up smiling at 7am and by 8am was on the roof of Timuk’s aunt’s house drinking milk with the locals. Today was “milk day” of the Joshi festival, so the un-pasteurized goat milk flowed like wine. After hanging for a bit with Timuk‘s relatives, we hopped into an old station wagon and were off to Rumber to enjoy the festivities. The crew consisted of Timuk, his brother, two of his cousins and his Muslim friend from Islamabad (Ahmed). The vehicle was uncomfortably packed with sweaty guys and live poultry. In the back of the vehicle were three live chickens that flipped out and flew around the car after each bump we hit. The situation was strange, hilarious and uncomfortable, but fairly enjoyable. It felt great to be part of something so unique and unusual. I was thrilled to be in a station wagon with a group of young Kalash men on the way to Rumber’s Joshi celebration. For the first day in close to a week, I felt healthy, rested, and mentally alert.

At 11:30am we arrived in Rumber. Rumber is located about an hour away from Bumboret by jeep. It is nestled away in an adjacent mountain valley, and is equally as desolately located as Bumboret. The extraordinary thing about the Kalasha Valley is that it is geographically hidden, and is located in a vast paradise of natural beauty. The main residence of the people of Rumber is a cluster of wooden houses located near the base of the valley. The festivals take place on top of a flat surface high on the hillside.

Rumber was glowing with exotic charm, as we drove up the final stretch of the trail.

Beautifully dressed Kalash women lit up the dusty mountainside like Christmas tree ornaments. Their colorful and radiant appearance created an enchanted atmosphere of cultural pride and tradition. Rumber was much smaller than Bumboret, and appeared to be even less financially sound. Kalash villagers are very simple, generally poor people that seam to live a near poverty yet peacefully adequate lifestyle. They don’t have much, but their community is so tightly knit that they tend to take care of one another like a giant family.

I immediately noticed that the women of Rumber more commonly had facial tattoos than the Kalash women of Bumboret. The light blue facial tattoos of Kalash women were very small and simple: usually a dot or a dot surrounded by a small circle on their forehead, chin, and one on each cheek. Occasionally a woman would have a small V tattooed between her eyebrows.

After arriving in Rumber the entourage and I walked across a small wooden bridge and past a primitive but clever hydro-powered flower mill before arriving at Timuk’s cousin’s place. We greeted our friendly Kalash hosts by saying “Shpata Baba (to a woman)” and “Shpata Bya(to a man); this means hello/greetings in Kalash. The crew and I then sat down on the floor in one of the rooms and were soon presented with homemade apricot brandy. The strong brandy loosened my mind and enhanced my already euphoric feelings of happiness and cultural absorption. For the next hour and a half, we sat on the floor in a circle drinking Kalash moonshine and conversing like old pals. Timuk was the only guy in the room who spoke fluent English, but the other guys were able to ask me questions through Timuk’s interpreting.

By 2pm we were all starving, thankfully the women had just finished preparing and cooking the chickens we brought over; lunch was ready. We enjoyed a pleasant meal of goat cheese, pita bread and chicken before heading out to the celebration. My host insisted I eat the majority of the chicken; again I was bombarded with selfless and unrivaled hospitality.

The festival took place high up on the hillside of Rumber. The shade was scarce and the sun was beating down hard upon us. The Kalash women of Rumber danced around to the beats of drums, chanting quietly while visibly getting lost in the moment. They locked into each other shoulder to shoulder while dancing in a drawn out circle, skipping their feet in unison with awkward sideways steps. Near the dancing square was a large cluster of wooden shacks where people stood around, observed, and socialized in the unrelenting heat. I was not alone at the festival, there were close to a dozen tourists and professional photographers lingering around the dance circle. I felt that the photographers were at times a bit too intrusive and culturally insensitive. However, I had no problem sharing my cultural experience with these other people; it was obvious to me that everyone there that day was completely affected by the beauty, grace, and purity of the festival’s atmosphere.

I returned back to my guest house not long after nightfall and spent the rest of the evening writing in my journal on the front patio. The moon was bright and the stars magically lit up the sky in a very special way. A group of Muslim men with long beards and dusty faces sat beside me talking amongst themselves and smoking hash cigarettes.

{They empty their cigarettes, roll bits of hash into the tobacco, reload the cigarette and smoke away}

I had a hard time sleeping that night; I could not stop thinking about my recent experiences. I was profoundly impacted by the last two days, and will never forget their significance. I was incredibly lucky to have come across Timuk at the jeep-station in Chitral, and to have been introduced to the Kalasha Valley. I have no doubt in my mind that I will return to the Kalasha Valley someday.

5-15-2008

I woke up early, grabbed a quick breakfast and was in a jeep headed to Chitral by 6am. I arrived in Chitral at 8am, and proceeded to hike to the main bus station about a 20min walk away. At 8:40am I was on a bus headed to Peshawar 12 brutally painful hours away,………….thankfully I was blessed with the worst seat in the house. I was seated in the far back corner of the mini-bus, the invasive wheel well took up pretty much all the potential leg room, it sucked……………

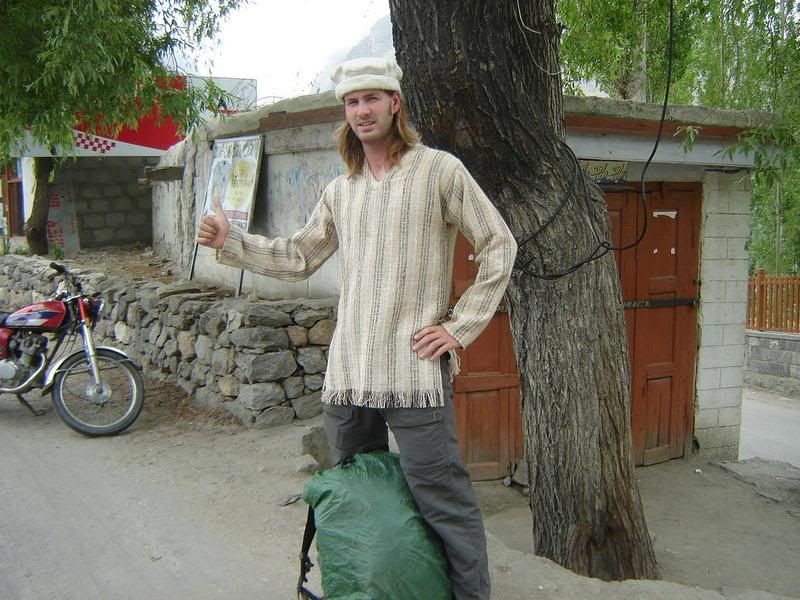

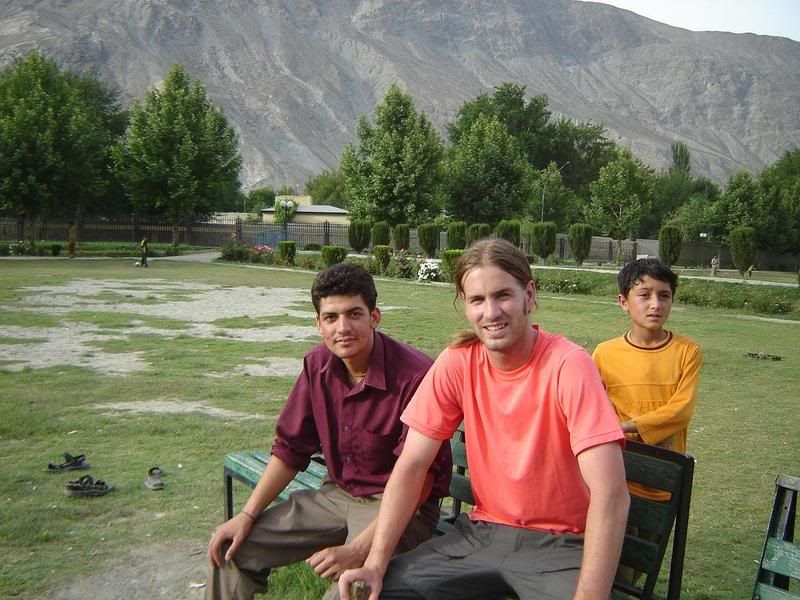

Here are a few pics:

40km past Gilgit

Batman kid:

Village kids on the mountain pass between Gilgit and Chitral

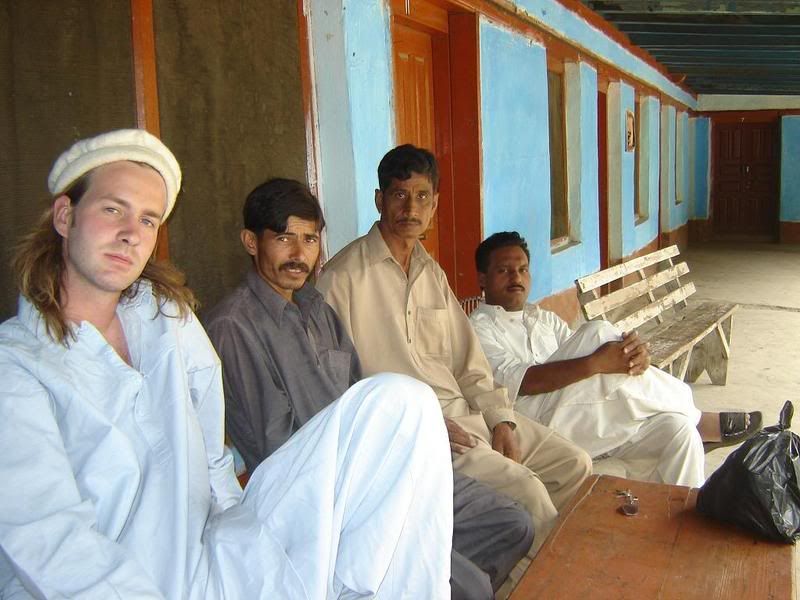

Guest house crew

The trail going into the Kalasha valley

Ayun Villagers up

Women of Bumboret down.

Trail into Bumboret UP

Bumboret kids:

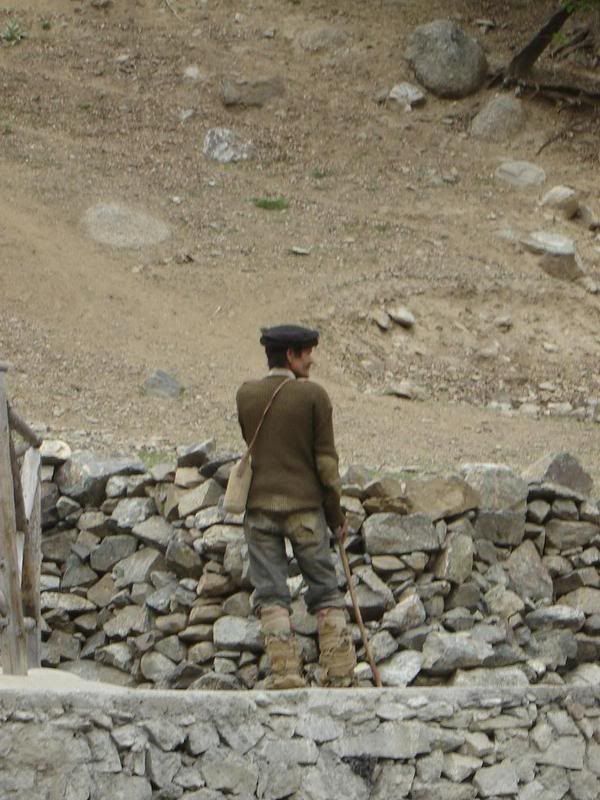

Kalash Shepherd

Old Kalash woman training the youth, Bumboret

Kalash women with mountain flowers

In the residential area of Bumboret

-Timuk's sister and child at his home in Bumboret:

Timuk, and his aunt at her home:

The Kalash crew in Rumber:

Rumber:

Rumber Villagers:

Hydro-powered flower mill in Rumber: