Afghanistan Part 2 - The Daliz Pass

Day 1)

June 8, 2009-

Sarhad e Broghil, Population 548. -elevation 3,400M or 11,154 ft

The lingering effects of food poisoning have left my body in poor shape. I am tired, my body continues to ache, my appetite is minimal, and my muscles feel heavy and weak. Despite this, I must put on my 65lb pack and begin the trek I have spent the last four months planning. As I stand in the tall wet grass beside the guest house, I feel antagonized by the imposing nature of the snow capped peaks that majestically surround me. I feel the adrenaline building up in my veins…….. I can hear adventure, discovery, and experience calling me with a seductive whisper from somewhere beyond the majestic rocky curtain known as the Daliz Pass(4,277M or .

Despite the lingering effects of food poisoning, and diminished oxygen level in the air, a result of the relatively high altitude of Sarhad, I slept fairly well. Excitement and anxiety pried my eyes open at around 5am. Soon after, our host served us a breakfast of flat bread with thick buttery tea before pointed us in the direction of the Daliz Pass. Filled to the throat with dense flat bread and salty tea, we began walking toward the barren mountainside. Our intended destination was a camp ground for nomadic caravans called Barak. Barak was located ten miles from Sarhad, and was unapologetically obstructed by the Daliz Pass (14,000+ ft). Day one of our trek turned out to be a long one, it provided us with several important lessons and an experience that neither my brother nor I would ever be able to forget.

As Toby and I slowly dragged our feet up the muddy mountainside, across the shallow streams and through the thickening snow, our lungs began to feel the strain of the thinning air. It was not until we neared the top of the first snowy ridgeline that I was able to coerce my brother to admit that the altitude was in fact wearing him down. This is the same guy who adamantly refused to wear sunblock because he was brown, and didn’t need it ( more on that fallacy later). By the time we had arrived at what we had hoped was the saddle of the pass, we were hopelessly fatigued, dehydrated and thoroughly discouraged by the incessant gusts of wind that ripped through our morale and pierced our cotton shirts like shards of frosty glass. At around 12:30 we employed the shelter of a large overhanging rock to escape the torment of the wind long enough to choke down a lunch of stale flat bread with raisons and peanut butter. The altimeter on my watch said 13,246 feet.

Shivering now, paradoxically soaked to the core from perspiration, we pushed forward up the thick muddy trail and through the knee high snow at a progressively slowing pace. Because of our fatigue, and our lack of acclimatization, we were not able to take more than 15 steps at one time before pausing to suck enough oxygen from the air to continue. The air became increasingly thin and our bags seemingly heavier with each agonizing step. We eventually made it to the top of the Daliz Pass; a flat snow field intermittently speckled with large patches of thick grass and boulder clusters. The wind gusts across the soggy mantle of the Dariz pass were pervasive and cruel. As we scurried over the top of the pass, the wind cut through our wet clothing, chilling us to the core as it gnawed at our cheeks and ripped open our tear ducts with blatant disregard for our mounting fatigue.

The descent provided us with satisfying and much needed relief, it had become obvious to us both that our pack weight and the mountain climate were given far less reverence than deserved during the planning stage of our trek. The trail gently zigzagged down a steep barren mountainside and soon placed us at the base of a steep ravine with a shallow but rapid stream providing a vein of life to the base of the desolate gorge. According to our old soviet topographical maps that we acquired online from the UC Berkeley archives, this stream was a tributary to the Oxus River.

It was now late afternoon, and my brother and I were weighted down heavily by debilitating fatigue. Being the ox that he is, Toby was now carrying a pack that weighed in the ballpark of 70lbs (30kg); mine was around 60lbs. Regretting it now, my brother had earlier in the day agreed to carry a bit more than I; this was because I was still feeling feeble due to the previous days I had spent praying to the porcelain/dirt hole gods in Ishkashem and later Sarhad e Broghil. This generous gesture is one that Toby would soon deeply regret, but one that has left me forever grateful.

After a 20 minute break spent complaining and contemplating how it was possible that we had not made it to Barak yet, we hastily began discussing possibilities of deviating from the path that lie directly in front of us. The trail in front of us looked hopelessly steep and appeared to unfeasibly lead up the far side of the steep rocky gorge. Ill with fatigue, we foolishly convinced ourselves that the trail ahead would be painfully challenging for us to navigate; therefore, we were better off finding an appropriate alternative route. Option B was to assume that the stream at the base of the gorge would gently and directly take us to the base of the Oxus River, at which point we would simply follow the river upstream until reaching our intended destination, Barak.

Undoubtedly influenced by heavy fatigue and driven by optimism thickly saturated in blinding ignorance, we chose to diverge from the path and attempt to navigate the presumably less strenuous route that followed the stream down the ravine. In retrospect, I find it shocking that we were so irrational to have diverged from the physically intimidating, yet assuredly correct path to Barak . We hardly spoke as we slowly worked our way down the stream; in vain, we diligently scoured the rocky creek bed for any sign of a path. After an hour and half, the seriousness of our mistake began to fuse itself to our dense skulls with terrifying force.

It was after 4pm, we were exhausted, and feeling lightheaded and slightly nauseous due to our lack of proper hydration and acclimatization. The stream soon became more reminiscent of a small river; this was interrupted at times with a massive snow bridge that assumed the shape and function of a small glacier. Not only were the snow drifts becoming increasingly dangerous to cross, but the ravine itself became incredibly steep and difficult to traverse. After Two hours, it appeared that we were perhaps half way to the Oxus river; however, small waterfalls and melting snow bridges obstructed us from navigating the last 500 (estimated) vertical feet downward to the base of the river.

Going further down the steep gorge had now entirely lost its appeal. We were forced to put our heads together and to brainstorm options, or lack of. It was clear that continuing down the stream would be incredibly dangerous; furthermore, we began to realize that even if we made it to the river, there was a very real possibility that we would be trapped by the steep canyon walls and swollen Oxus River. If no trail existed due to high water level, it would be likely that our exit strategy would be an immense challenge, if not an impossibility under the circumstances. Our options were limited, we were so far down the gorge that getting back up with our level of fatigue appeared to be an impossibility; moreover, camping on location was also impossible, we were deep in a narrow canyon with nothing below our feet but an ice cold stream, melting snow drifts, and large loosely set boulders……….setting up a tent would not be possible.

Worn down and weakened by the lactic acid accumulating in our legs and backs and feeling suffocated by the cold thin air, our debilitating exhaustion made our heads feel spongy and lifeless like the cumulous clouds hovering above us. In this unfavorable condition, we made our second utterly imprudent decision of the day.

I noticed a shallow rockslide (gully) on the left side of the steep gorge. It appeared that the shallow rockslide was at a climbable slope, and if we could pull together enough strength to shimmy our way up about 150 vertical feet, perhaps the steep wall of the ravine would level out enough for us to set up a tent and rest for the evening. It seemed at the time to be a simple and logical solution to our increasingly worrisome predicament, a quick fix that would bring our day of trekking to an end in no more than 20 minutes…

Perhaps not surprisingly, the gully turned out to be more challenging to climb than we had anticipated. Even at the early stage, each step was both dangerous and exhausting. We slowly and methodically crawled up the steep narrow gully and though our feet slipped continuously on the loose rocks beneath us, we were able to cling to the jagged cliff wall and slowly pull ourselves up the gully at a respectable pace. We climbed ten feet at a time, with heavy packs (my brothers being at least 70lbs), and thin mountain air, any more than that would be an impossibility in our feeble condition. After each ten foot burst our legs and arms would turn to jelly and the lactic acid built up in our muscles would deliver to us a sharp burning sensation that would often make our muscles cramp and temporarily seize up. Each incremental segment climbed would make my heart beat so hard that I could feel the veins in my temples twitching with each pulsing beat. After a minute or so of gasping for air, and wallowing in physical and psychological despair, I would check on my brother, before forcing myself upward an additional ten paces.

At 150 vertical feet above our starting point, it appeared that our climb was coming to an end. At the 300ft mark, Toby and I began to internalize our emotions of panic and fear; I for one cannot remember ever feeling as desperate, afraid, and exhausted as I did on that mountainside. At about 500 vertical feet I became so exhausted and dehydrated that my head would not stop pounding, my heart was beating so hard that it made my entire body twitch with each beat; with every meter I climbed I would feel an overwhelming feeling of nausea and shortness of breath. The gully at this point was so steep that one slip would without doubt send me to my death; even more horrifying than my own personal despair and fatigue was my lucid understanding that if I were to lose my grip, in all likelihood my body would act like a bowling ball and knock my brother off the rocks below me. There was no doubt in our minds that if this were to happen, we would both weightlessly cartwheel down the cliff at an uncontrollable rate until reuniting with the merciless boulders waiting for us more than 500 vertical feet below. I could not stop thinking about how if my brother were to slip, it would be entirely my fault. Words cannot describe how absolutely horrifying it was for me to embrace this realization.

6pm…….we were both out of water……….we were 1.5 hours into our climb, the gully was no longer a gully. We were now climbing up the side of a cliff. The 60lb+ bag on my back ceaselessly pulled me away from the cliff, providing me with a constant reminder of my hatred for gravity and our ever more dire predicament. According to the altimeter on my watch we had climbed over 600 vertical feet. The ‘cliff leveling out’ mirage was incessantly cruel, leaving us feeling ever more devastated and hopeless with each increment of climbing. I constantly searched the Cliffside for any sort of shelf that would be large enough to fit our tent and shelter us from the snow that was now coating the rocks with an undesirable lubricant. Above and below us the steep rocky Cliffside sandwiched us into a nightmare of hopelessness and fear.

At 6:30pm I could not comprehend why the cliff had not given into the hillside………….when would it level out. The snow poured heavy upon us as the sun slowly disappeared. My hands became numb and the rocks slippery from the falling snow. My palms and wrists were now raw and bleeding from the hours spent pulling myself up the sharp jagged rocks. Toby kept begging me to take some stuff from his bag, but I selfishly refused, I just could not bring myself to even consider adding more weight to my bag. Despite this I could not stop worrying about his role in this dilemma. After every 5-10 foot shuffle upward I would call down and check on him, he would usually just ignore me and look at me with a cold blank stare. What the hell could we do to get out of this……………..the cliff would have to end at some point………..but would we have the energy and will to make it to the top without passing out, or slipping on the snow covered rocks?

At 7pm it was getting dark, and we were in the middle of a snow storm. I told my brother that I could not go any further and that we should just climb into our sleeping bags and tie into the rock, or perhaps tie our tent to a four foot wide slanted rock ledge I had found. We needed to think of something quickly, time was running out, and I was becoming increasingly worried that my brother or I might lose consciousness, and allow gravity to pull us off the cliff. Toby would not entertain either of those ideas, saying it would be impossible to make it through the night that way due to the wind gusts and snow.

I continued to climb with determination to endure, though my nausea began to worsen and my head continued to throb. Toby sluggishly followed below, following each of my steps about ten feet beneath me. I felt a glimmer of hope after spotting a large jagged rock that protruded about ten feet from the edge of the cliff. The rock was about the size of a truck and lay about fifty feet up from us and off to the right around forty feet. It seemed plausible that the upper side of the rock would perhaps contain a large flat surface. We were now more than 800 vertical feet above our starting point. I felt like crying, helplessness and vulnerability was overwhelming us both. I fought hard to maintain enough motivation and optimism to escape from this situation. Having my brother below me and in such a dire predicament provided me with an ample amount of determination and incentive to continue climbing.

The other end of the large rock proved to be less than helpful as a potential camping spot. However, from this rock it appeared that an area fifty feet to the right, and seventy five feet up the mountain was an area where the cliff gave into a more gradual, but steep hillside. Toby and I pushed forward with excitement and anticipation, our misery would soon end. At around 7:20pm, Toby and I were out of the gully and standing on a steep hillside.

Feeling elated and comforted by our newfound ability to physically stand without the guidance and support of our frozen hands, Toby and I looked at each other and smiled. We cut sideways to the right along the hillside another 75ft until we came across an area level enough to pitch our tent. The snow had now stopped, the wind had thankfully subsided. After clearing away a small area, Toby and I used sharp rocks to cut a flat spot in the hillside. Toby in fact did most of the digging, each time I bent over to dig, I became overwhelmed with lightheadedness and nausea. I instead used my boots to clear away the sand that Toby had dug up ( I was basically worthless during this entire task). We set up our tent and were in bed by 8pm.

Toby and I were both incredibly dehydrated, and were far too exhausted to consider cooking. Instead, we treated ourselves to a scoop of peanut and handful of raisins each…………it was delicious. During our in-tent debriefing session, we solemnly promised ourselves that we would be more careful, and only make prudent and well thought out logistical decisions.

I shivered through the first half of the night, but eventually was able to heat my core enough to lie comfortably and fall into a semi-conscious slumber. Neither of us were able to actually sleep, our stomachs ached with hunger, our throats were dry and course from dehydration, and our muscles cramped and ached each time we attempted to readjust ourselves in the tent.

At two in the morning, when exiting the tent to use the penthouse toilet, I discovered that the tent was covered in 2 inches of fresh snow. Seeking to capitalize on this gift of nature, I quickly filled our water bottles and aluminum cooking bowls with snow and placed them in our sleeping bags so that we could melt enough snow to rehydrate ourselves. Within an hour we were able to hydrate ourselves with cold refreshing water. I continued this routine about every 2 hours until morning.

-June 9, 2009-

As the sun began to rise we slowly became aware of where we were. At 7am we saw a caravan of Yaks 100 meters above us. We had camped directly below the trail. We had learned our lesson and vowed never to diverge from the trail again.

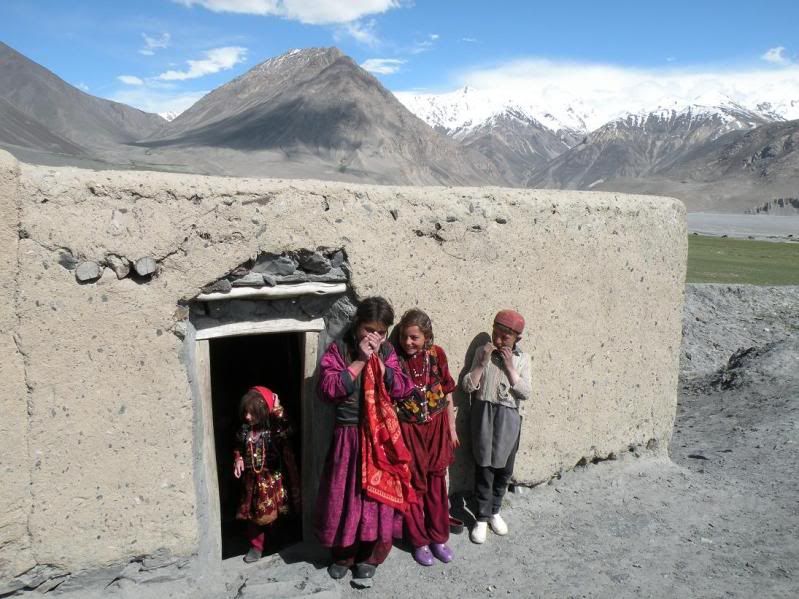

Leaving Sarhad:

Going up the Daliz Pass:

The first saddle:

The end of day one- Toby cooking breakfast the next morning (the snow had melted by 8am)

A video of our camp spot: